Introduction

Depiction, the urge to re-image sights and experiences, be it visually or aurally, is an essential part of our existence. For our ancient ancestors, it did not suffice to simply find shelter and safety in caves, the caves had to be decorated with their experiences as well. Since the first sapiens began to tell stories, they also started to depict them with ochre and other materials on limestone walls.

A common trope in many of the stories we have told through the ages is the idea of a hidden treasure—a pearl of great price, a chest full of pirate’s loot, gold coins and gems in a dragon’s lair. We have always intuited that the earth on which we stand holds deep secrets within it, secrets worth seeking out, perhaps secrets that find their counterpart in deep crevices of our own consciousness.

In his work Díðrikur Doves and Other Hidden Treasures, consisting of ten luminous cave- painting for Sandoyartunnilin, the new sub-sea tunnel connecting the islands Streymoy and Sandoy, Edward Fuglø plays both on this ancient urge to depict what is seen and heard and on what wonders we might find if we only dare to dig deep enough.

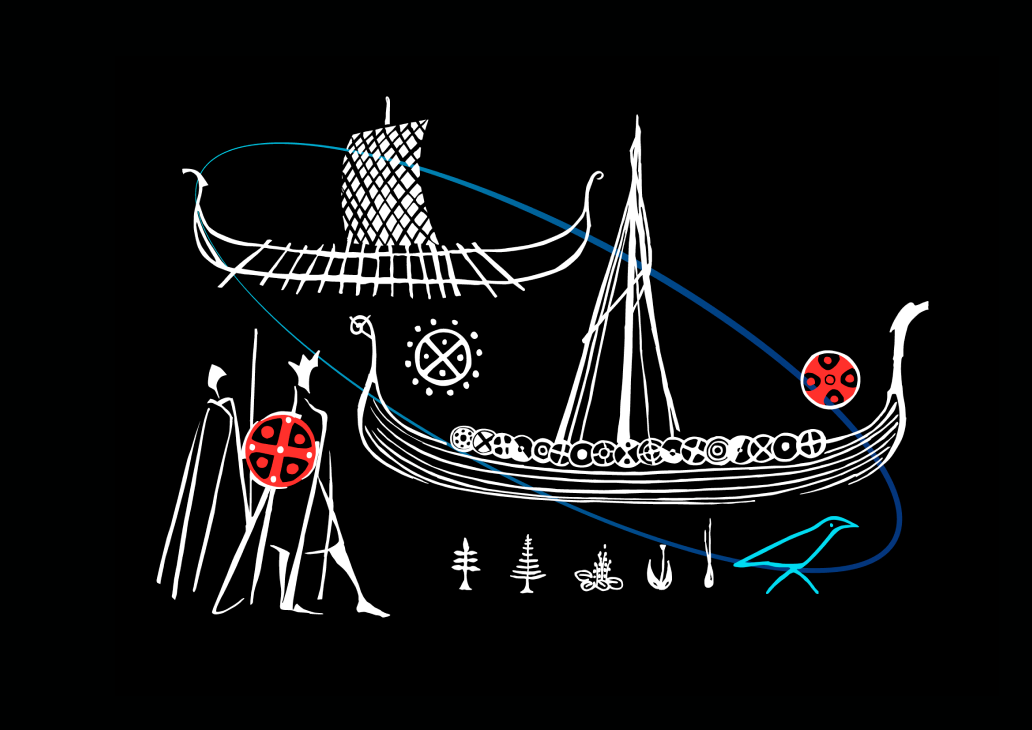

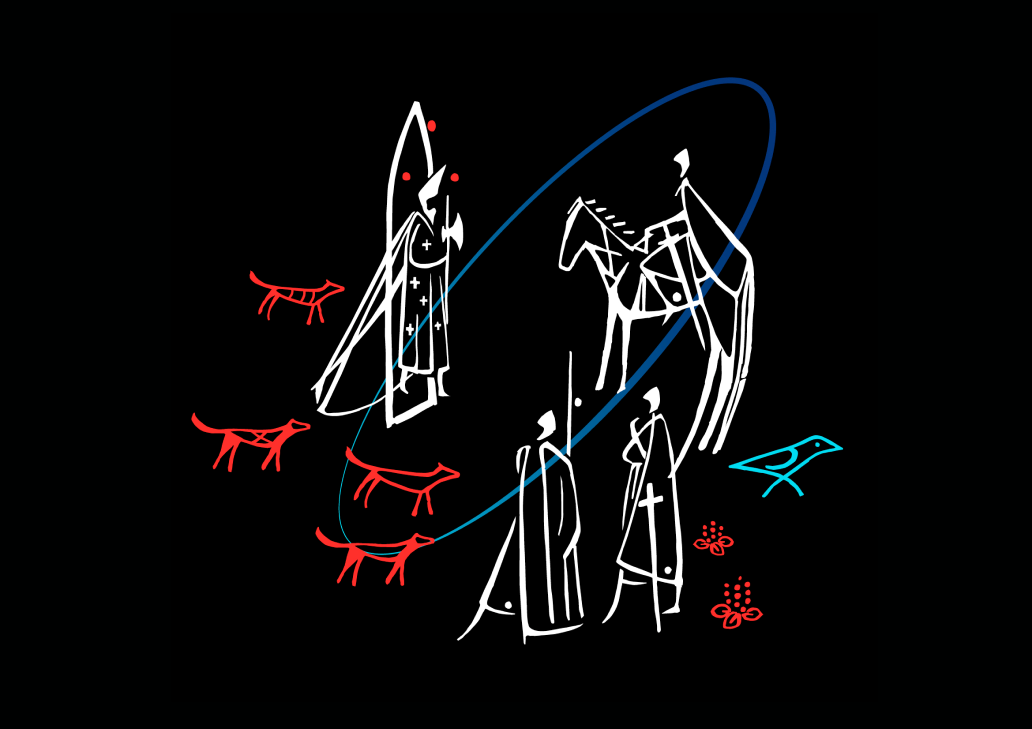

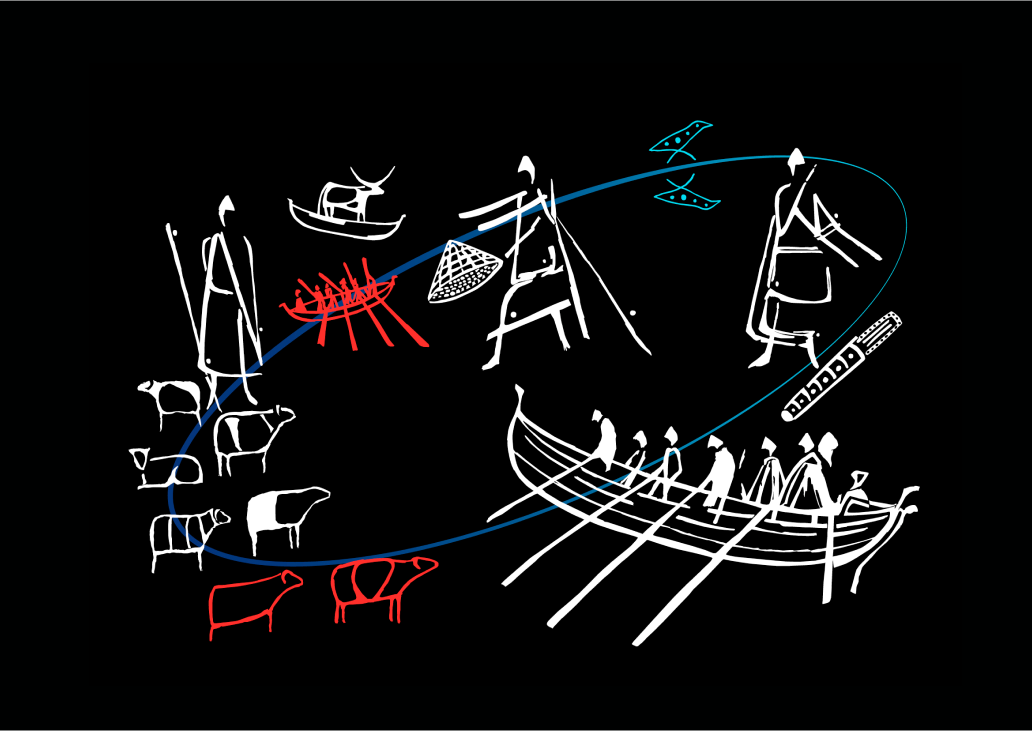

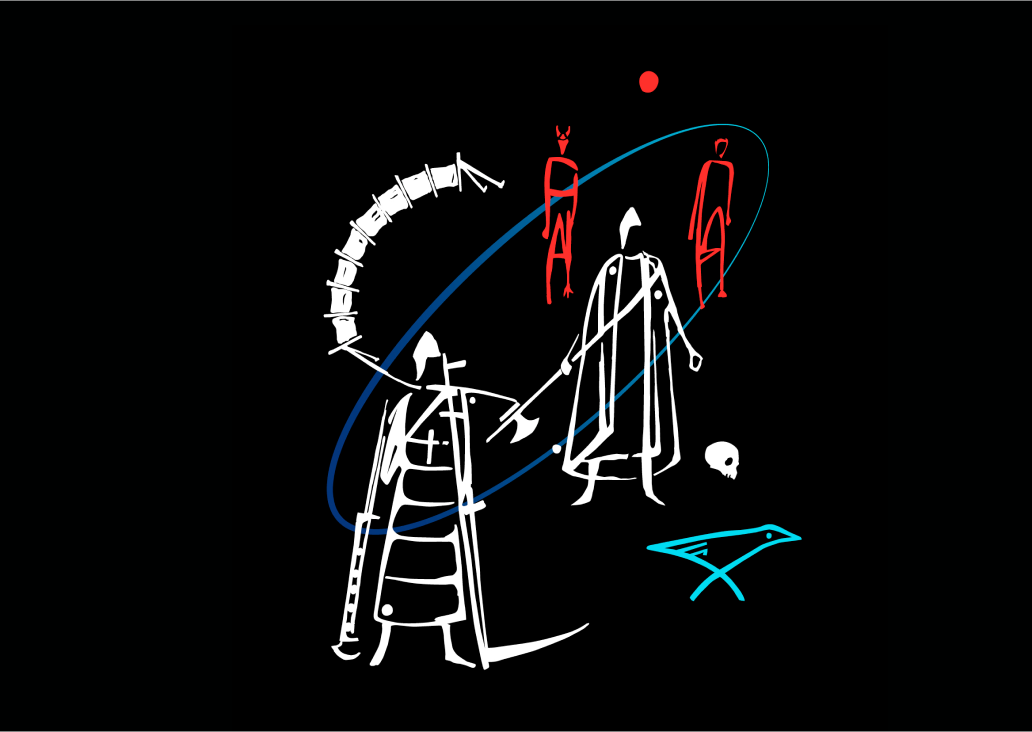

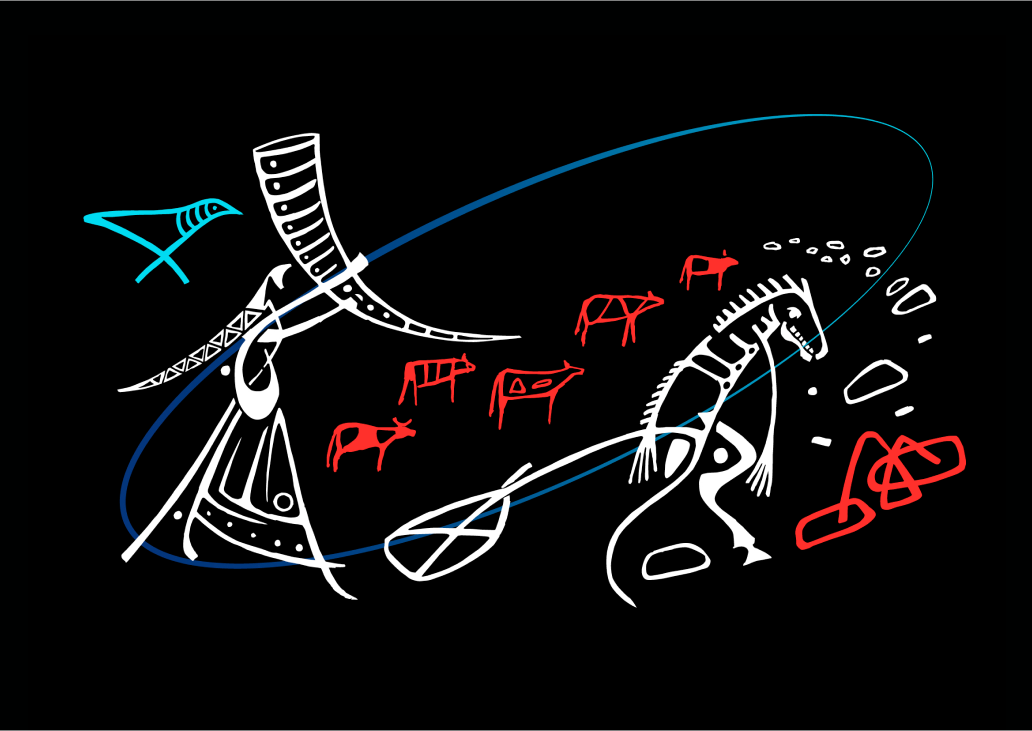

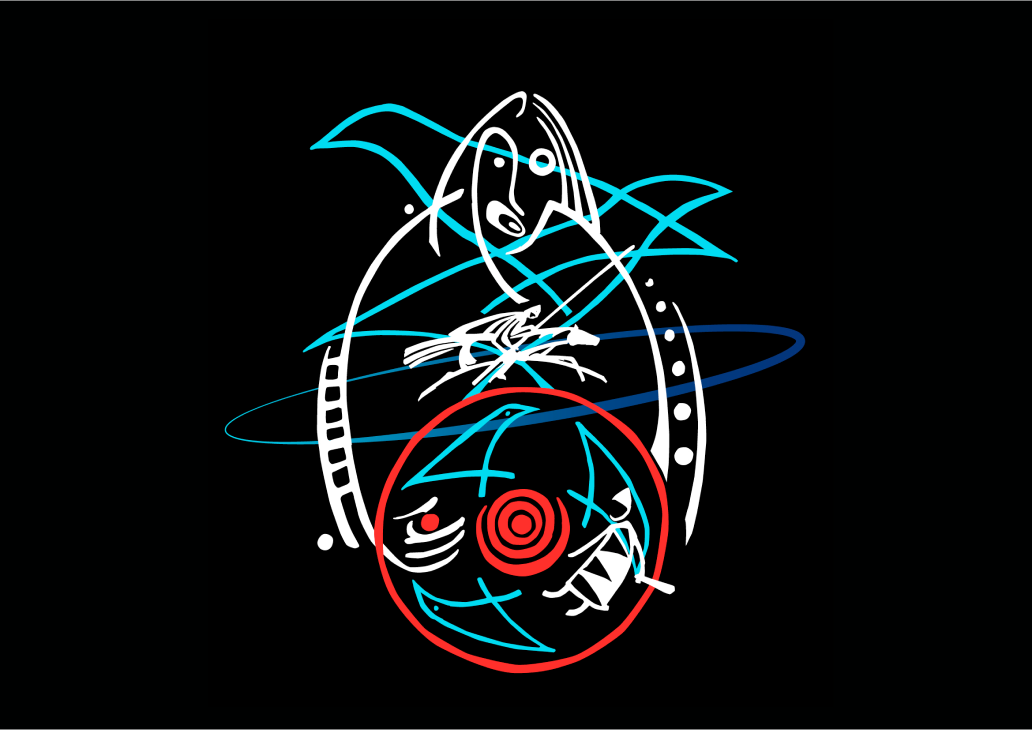

What happens when we drill such a modern marvel of a hole as Sandoyartunnilin, through which cars can drive while ships sail the seas above them? As has happened so often before, secret treasures are found. This time, though, it is not coins, pearls and diadems that the subterranean world has hidden, but stories depicted in light. The lay-bys, cavernous enough that large trucks can turn in them, are the tunnel’s caves. When they are excavated, cave- paintings are found on the walls—though these are not ochre on limestone but luminous red, white and blue lines dancing over black basalt. Light pictures shining in dark caves.

Their motifs are the stories of the two places connected by the tunnel, the historical village of Kirkjubø and Sandoy. Stories laced with legend and myth—of powerful and wily clergy that suck the life-blood out of common people and of steely women finding their way in a world dominated by men, of angry witches cheated out of their gold and of huldres, those grey folk who live inside hills and boulders and who would leave ordinary humans alone if only they’d stop meddling in their affairs.

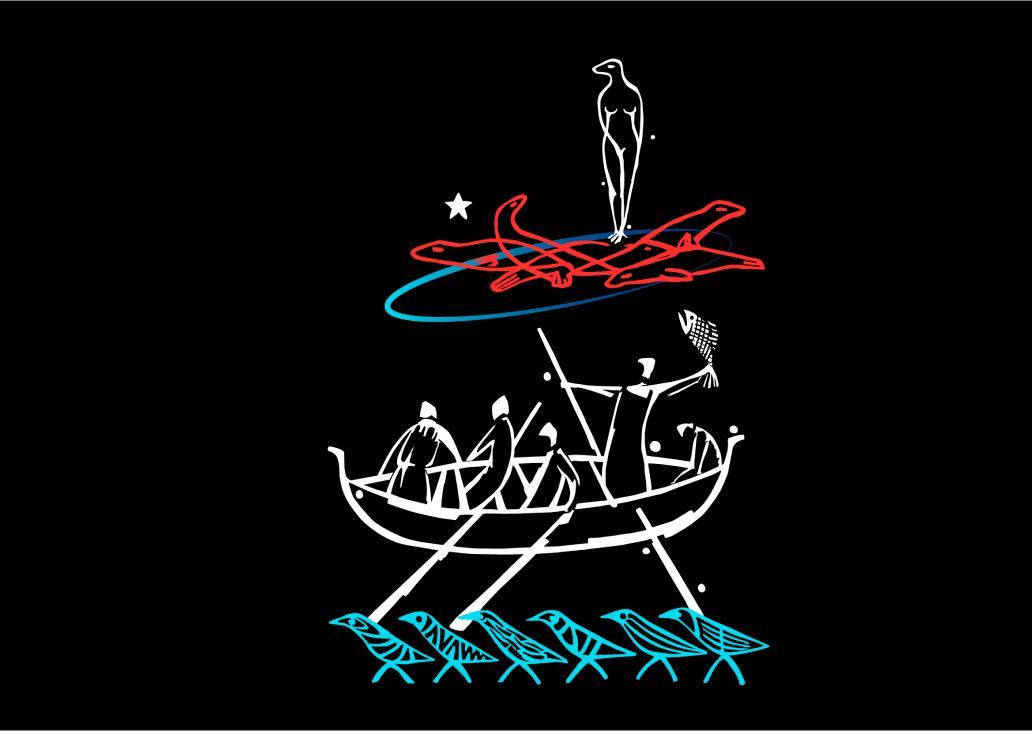

As you drive through the tunnel and discover these treasures on your own, you notice some birds trapsing through the various folkloric scenes. Most often they appear alone, but once in a flock, and in a couple of places so over-blown that at first you think they are but abstract flourishes. But these birds, what are they? Perhaps doves? Yes, doves indeed, but no ordinary doves, they are Díðrikur doves, something you realise when you see the last cave painting. Its strokes of red, blue and white light depict Díðrikur of Skarvanes and some of the multi- coloured birds he painted in the first half of the 19 th century. Díðrikur is the first Faroese painter that we know of—visual arts are young in the Faroes!—and all the extant works by him are of birds: hens and cocks, and many doves. To Fuglø, as he reworks Díðrikur’s magical many-coloured birds, they become their own unique species, Díðrikur doves—the colourful birds of the imagination that Díðrikur let loose as he unleashed Faroese visual arts. As Fuglø uncages them, lets them fly out of their allotted place, they roam the tunnel and travel back through time, settle in the various beaming depictions of villainous priests, fierce women and mythical creatures centuries older than the birds themselves. They are a leitmotif that binds the tunnel’s ten luminous cave-paintings together, making Díðrikur Doves and Other Hidden Treasures Fuglø’s homage to Díðrikur of Skarvanes, the humble farmhand who became the pioneer of Faroese visual arts.

Light is Fuglø’s medium. The technique he uses is well known from theatre, gobo lights. The image is cut out in a stencil and coloured. The stencil is placed in front of a light source, today often a LED projector, casting a razor-sharp image on the surface, in this case the uneven rock wall of the tunnel. In order to achieve the desired effect, getting the luminous image to play well with the lay-bys’ walls, Fuglø and his team tested the gobo images over and again in the tunnel, adapting the compositions, dimensions and colour combinations to precisely fit the images to the particular surfaces they are to occupy.

We who travel at high speed through the tunnel are like Díðrikur doves. As we drive though this marvel of modern engineering, back and forth between Sandoy and the mainland, we too journey back in time when these luminous cave paintings beam back at us. Most of us fly by them in a flash, notice only some bright white, red and blue lines that give shape to a picture. We enjoy it, glad for the amusing distraction and forget about it. And that is fine, it is part of the purpose. But perhaps some of us wonder: Who is that one wielding an axe or why does that crow fly off with a knife in its beak? And we want to settle down, like a Díðrikur Dove, and enter the picture, enter the magic of its story. Of course, neither an easy thing to do nor recommended when you hurl along at 80 km/h in a heavy metal box. But we still can let the images linger in our imagination and when sedentary again, look them up on the Internet or pick up this booklet and explore the tales these light paintings depict. Perhaps we also, like those doves, will find our place in the stories. And we are grateful that we do not only have clever engineers that can carve hi-tech holes under the sea for us to hurry through but also have artists like Edward Fuglø who dig deep into a collective imagination and unearth tales and depict them anew. For us as a species it is not enough to have caves and holes, it seems we cannot live without the tales that we can decorated them with.

Poul F. Guttesen